The dust swirls up in the air and then down again, just to land underneath another set of tires. The sun is at its hottest now. Cars spouting. The drivers don´t hesitate to use the horn. The two boys sit in the back of the scrawny tempo (a kind of moped and bus mixed). Before it has stopped, they have already slid off and come running towards me. Krishna and Rajendra are brothers, only nine and ten years old. After their father injured his leg in a flood, an officer in their village sent them into town to beg. The mother is dead. Little dirty hands are held up.

- One rupee, Madam, one rupee!

- Hey, what’s your name?

Uncertainty. The two of them twist and scratch their dirty clothes. Their noses running under large children’s eyes.

- One rupee, Madam.

- – What do you think about begging, I ask Krishna and Rajendra who are eagerly keen to study my camera.

- – We don’t like it, but we have to do it.

- Big Brother Krishna suddenly becomes lively. – But we certainly don´t want to go to school. The little one nods eagerly.

- – No, we certainly don’t want to.

- – Where are you going now?

- «We’re going by tempo to Jodibuti and we’re going to beg on the road.

- The boys smile as they run off, ten rupees richer.

Krishna and Rajendra are just two out of many. Every day children are coming to Kathmandu to find jobs, many of them experience exploitation and choose a life on the street.

Kundura (16) works as a tempo assistant and picks garbage that he sells. He has been living on the streets of Kathmandu for three years. His background is typical of those who live on the street.

- My father drank and beat me. Finally, he tied me up with wires and beat. When I was unleashed after that, I hit him in the middle of his face as hard as I could, and then I ran off.

Kundura beats with his fist into the air to show how hard he beat his father in the middle of his face. He smiles happy. His pals nod silently. They haven’t wanted to tell their stories. Kundura is the only one who wants to tell why he landed here.

- Then I took the vegetable bus to Kathmandu. I came here at four o’clock in the afternoon and slept out at night.

- Why did your father beat you?

- He was angry and I was angry because he used to beat me.

- Have you traveled to the village since then?

- No, never, not once.

- Do you miss the village?

- Yes. I was born in the village, I like the village. But now I like Kathmandu.

- Do you want to go back to the village?

- No, I’m too lazy to do that.

- It is perhaps too expensive too?

The pals laugh well. Kunduras´ village is just outside Kathmandu. It costs under a dime to go by bus there.

- No. That’s not why I’m not leaving.

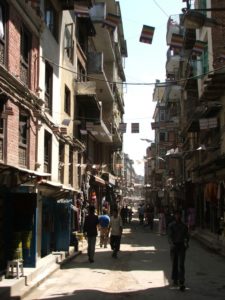

In a small brick house in the dust-filled center of Kathmandu 20-30 street children are gathered to learn photography.

Deepak has shown up with his two best buddies, Maira and Anir on thirteen and seventeen. Deepak is the oldest of them. He is 22 years, has wild, curly, uncombed hair and wears a filthy orange T-shirt with a big picture of Britney Spears.

- I said he was too old to come today, but then he got this weird look on his face, so I hurried to say that it was okay, says Rewat Raj Tumilshina, the ex-street boy who along with three buddies runs a center for street children called «Our World». Rewat landed on the streets after an episode where he was beaten by his mother. His parents argued a lot and divorced when he was five years old, which is very unusual in Nepal. After many years, he joined a rehabilitation program and was supported to start the street children Center «Our World» where he himself would be the role model and help children who live on the street.

Deepak and Anir decide pretty quickly to go to Bolka, a storage place for rice, grain, fruits and vegetables which arrive with trucks from the villages. At Bolka there is also garbage. Garbage, litter and again garbage. Tons of garbage as far as the eye can see.

- See where you’re going! Rewat says. Around my sneaker knughs a half-crushed bottle. In between the garbage lies the remains of a buffalo. I look worried at the boys’ thin plastic sandals as they run away from us.

- There, the boys are crying thrilled. There!

A little girl walks around in the filthy river looking for paper and plastic. She’s got half-length hair and dirty clothes and can’t be more than ten years. The grey, poisonous Bhagmati river contains ten times higher pollution than desirable and is filled to the brim with old garbage flowing. Around 4000 Nepalese children work with garbage. They pick plastic, metal and glass bottles and are very prone to cutting injuries, infections and dog bites. Many of the dogs here have diseases, like rabies. Children also easily become ill because they work in the most polluted parts of the city. All the boys cough, but Maira, the smallest of them, coughs the most. A rough, sore cough. The fine particles of dust get sucked into the lungs and can in the long run cause diseases like asthma and cancer.

Deepak takes the camera and fires away.

- Now it’s my turn, Maira cries out thrilled.

Maira gets his chance. Snap snap. But then the two mates stop, looking at the camera like there is something wrong. After a while they come back to us.

- It doesn’t work.

- Doesn’t it work? Rewat says and takes the camera to look at it. Before we know it, he’s taken out the camera film to see. Oh, no! All the pictures ruined.

On the sidewalk outside the photographic store, Rabindra sits down with his forehead in his hands and stares down at the asphalt.

- He is depressed because it was he who destroyed the camera, Deepak says. He and Anir try to play with Maira and say it´s ok, but Maira can’t smile now.

We go back all the way to the garbage sorting facility and further up the river to Kalimati, the big market. Here there is full activity; shelters bursting with the most amazing merchandise and sellers who scream with great baritones what they have to offer. Children’s hands rapid sort the various items in and out of sacks and boxes.

Maira follows all the time right on the heels of Rewat. If Rewat takes a step to the right, Rabindra does the same thing. If he stops for a moment, Maira does the same. Jitendra and Anir are discussing where it’s a good idea to go. But suddenly they begin to walk in opposite directions. What’s going on? Soon they stop. Shout to each other. Not long after, they’re back on the heels of each other.

An elderly man lays on his back on the sidewalk. He’s looking dead.

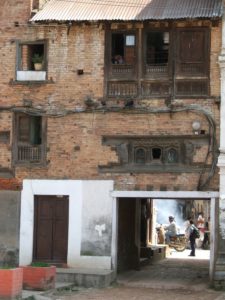

- Here I used to live, Rewat says as we pass by.

- Look, I say horrified and point. – Is he dead?

- No, he just sleeps, Rewat says and laughs.

- Do you have bad memories from here?

- I have both good and bad memories from here, he says thoughtfully.

- You escaped from home?

- Yes, I escaped.

- How old were you then?

- Six years.

Rewat becomes quiet. We agree to go somewhere to grab a bite. Before entering the small sidewalk restaurant, Anir, however, has disappeared again. Rewat looks worried.

- He’s a little different that boy, he says.

But Anir follows us all the time with his eyes from afar. When he sees that we are standing and waiting for him, he suddenly pops up from nowhere, just as quickly as he disappeared.

We sit down in the corner of the restaurant. Then Anir goes and get seated at a different table. He refuses to eat anything.

- I don´t like to eat in such places.

Rewat looks at me.

«I want them to learn such normal things,» he says. How to behave together with ordinary people.

Eventually, Anir comes and gets seated close to Deepak. Then he lays the chest over the table and holds his hand in front of his mouth.

- What do you think about this life?

They all become quiet and look at each other.

- We don´t know, really, Maira says with an innocent look.

- What do you think of him, then? I say and point at Rewant. Anir mumbles something, his hands in his face.

- What? What does he say?

- Ramro, Maira says. – He is good.

The children dine. But Anir only takes some water.

Most street kids never go home again.

- Look at us, Rewat says and point to his pals. – We’re not going home neither. We have looked after ourselves all the way, earned money, gotten us food and roof over our heads. Why should we go back now? We might go to visit, but that’s all. In this small house we can have up to ninety children at once! Why? Because we care about them, because we understand them. To succeed in this field you really have to care for the children, he says.

The children are anonymous in this article.

Kathmandu, May 2005. Research: Jitendra Bajracharaya, Bhupendra Basnet and Margunn Grønn