Kathmandu is normally loud and noisy, but today everything is quiet. Nobody knows how long the curfew will continue.

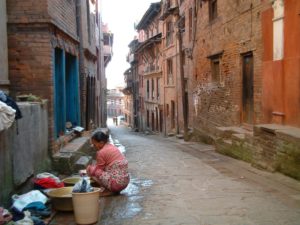

Today is the third day of curfew, everyone stay at home and it seems like the whole city is asleep. Actually, it is so quiet I can sometimes hear the roar of the elephant in the Zoo close to where we live. Sometimes we see people on the top of their roofs, looking around at the dead city, only some dogs barking and birds flying around. People who have gardens may sit outdoors, but they are also quiet today. The only activity I can see is when someone is hanging wet clothes to dry on top of their roofs. It really is a dead city. The only thing we can hear are choppers and people turning on their radios when Radio Nepal is transmitting news in the morning and afternoon. We saw one aircraft yesterday leaving Kathmandu, and heard another one today which I could not see. Yesterday we also saw a military jet.

Yesterday afternoon the government lifted the curfew for two hours between 5 and 7 p.m. It was crazy, the whole city of Kathmandu was suddenly on its feet, people were moving fast to the shops to get groceries (or to open their shops), cars and bikes were moving, the streets were full of people, there were lines everywhere. I never experienced anything like it. We were following the news carefully the whole day, afraid to lose the opportunity to go shopping for groceries in case the curfew was lifted. But it really was no problem, because at five o clock the whole town was totally changed within a minute. We walked restless like the others to find a place to buy babyfood, rice, wheat, beans, lenses and all the things we think we will need if a serious situation occurs. I think white people must have been more worried than nepali people because I have never seen so many white folks here at the same time. And the shopkeeper smiled from one ear to another as we left the shop, having emptied our pockets for all our money.

This morning the curfew was also lifted from 6 a.m. to 9.30 a.m. Everything suddenly seemed to be back to normal, people seemed happy and smiling, more shops had managed to open since yesterday, drivers were using their horn like it was some kind of celebration. I relaxed at home with my twisted ancle, while Gard and Kristoffer went out for some air and another big sack of rice. We are talking about what we will need or not in an emergency situation and how it might be. We don´t know how long the curfew will continue. Some people think the curfew will go on for days, others think it might be over on Sunday.

Our didi, Tirta, is telling how people were fighting to get water from an outdoors tap yesterday morning when the curfew was lifted for limited time. And yesterday evening on tv we could see people trying to fill their kettles and casseroles with water dripping from a tube in the rain. Today it was better and more relaxed, Tirta says.

Kathmandu, September 2004